YOU BELONG TO ME

by Maya Hristova

·

By Maya Hristova & Katažyna Jankovska

Geistė Marija Kinčinaitytė is Lithuania born, London based artist and researcher, currently undertaking her Ph.D. in Film and Screen Studies at the University of Cambridge. Her image-making practice is defined by encounters with the eerie, which is understood to be both the cessation of a comfort zone — whether self, human, habit, habitat, milieu — and alertness to a yet-to-be-identified presence. While mainly working in photography and video, she welcomes collaborations with the writers, composers and other artists who share similar interests in exploring the unknown.

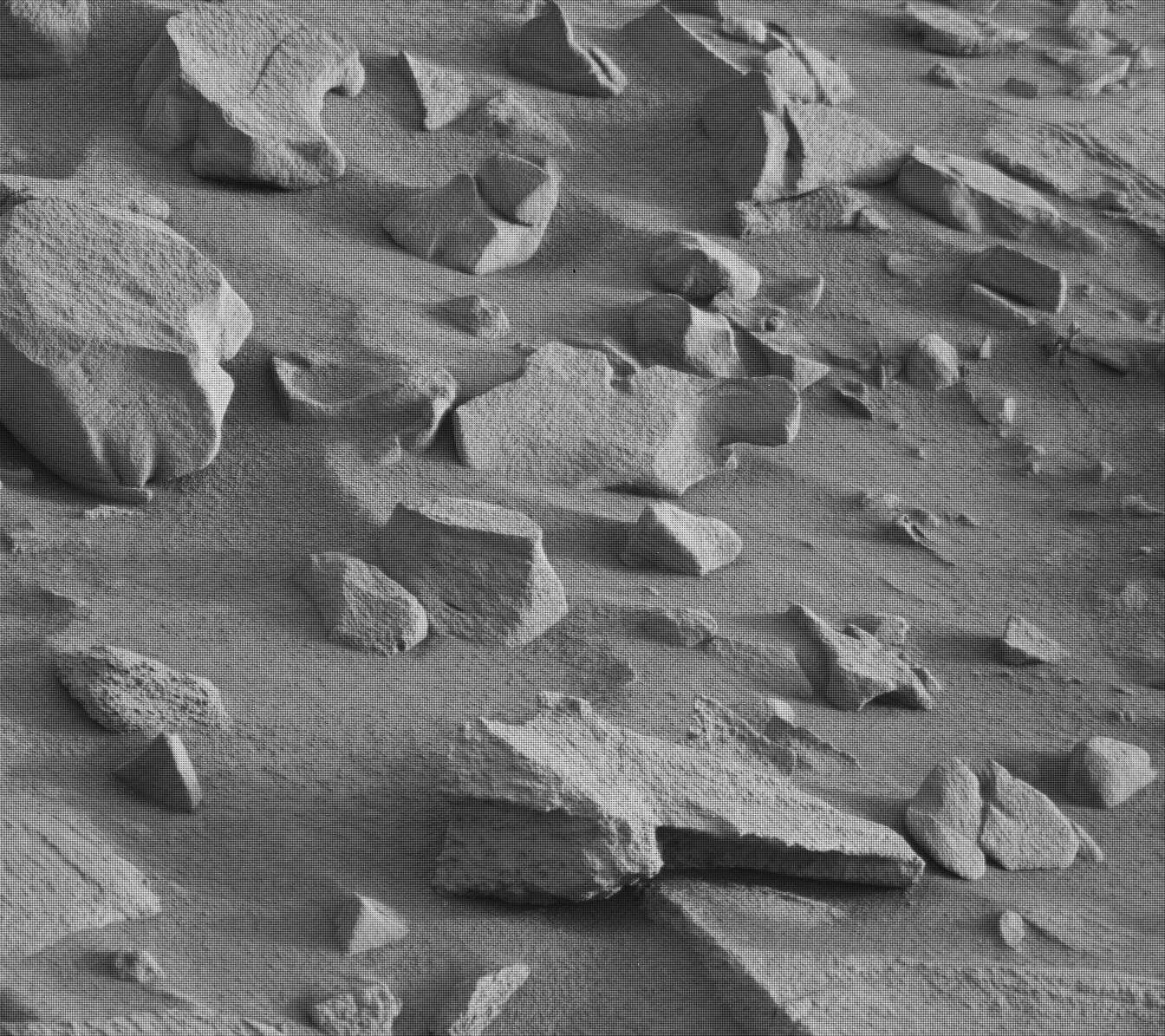

In her project "You Belong to Me" (book), the artist questions the role of visual images in claiming and occupying a territory, body or planet. In it, she uses images of the surface of Mars taken by NASA rovers and combines them with her own analog photographs of Icelandic landscapes to draw attention to the image-shaped anthropocentric reality of the distant planet and humans' supposedly subconscious desire to occupy it.

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist

In your project "You Belong to Me" you use images of the surface of Mars taken by NASA rovers equipped with visionary science instruments, and juxtapose them with your own analog photographs of Icelandic landscapes. Could the project be understood as a visual experiment that questions our ability to differentiate between human and non-human photography, home, and alien landscape?

The intention wasn't mainly to comment on the differences between human and non-human photography or different landscapes. At that time, I think I was more interested in the materiality of the image as the document. For example, the accidents that emerge in these visual scientific documents which capture or simulate the surface of the Martian landscape. Here, the glitches, sand storms, shadows, transmission errors appear as some obstacles that allow the opposite of an immersive illusion that the imagery shared by NASA of high-res landscapes evokes (now even 360 degrees view).

My interest in working with these images was stimulated by their promise and failure of representation, as well as their impact on the imagination saturated by the landscapes that cannot be entered but are already 'occupied' by the gaze.

I guess it naturally turned into a visual experiment because of the mixture of the Icelandic and Martian landscapes that share the eerie presence of a barren landscape, and the permeating impossibility to distinguish between the alien or home landscapes because of the high-res quality that these images share. Removing the color from some of NASA images allowed me to access that landscape as something familiar, while the Icelandic landscape became more alien and removed, a document from elsewhere.

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

While letting us gaze onto other planets, you also engage us to rethink our relationship to and with our own planet. Is a sober perspective on our species as a whole only possible through the appropriation of such a "non-human" perspective?

I think de-centering is a vital act and process which allows us to rethink and feel through, including our relationship with the planet we are currently occupying, as well as the expansion beyond it. However, even if there is an attempt to get closer to the 'non-human' perspective, it is already perceived through the human point of view. These more or less successful appropriations of the non-human perspective allow measuring and expanding beyond defined boundaries, leading to an impulse, an impact or a feeling, which is unfamiliar, therefore creating space for a new sensation, perspective, thought.

By juxtaposing these images, I think it was my subconscious desire to create a space for dissonance, which would open a thought process inviting a shift and shuffle of dominant positions regarding what is known, familiar or the opposite.

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist, Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

In your practice, you question the importance of images that form our perception of distant and yet unknown spaces. In "You Belong to Me" you draw attention to the image-shaped anthropocentric reality of Mars and the desire to occupy, at least with a glance, the territory man has not yet had the opportunity to face directly. In her essay "On Photography" Susan Sontag claims that "to photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed". Isn't the emergence of these "inhuman" images the first step toward colonizing the planet?

Remembering a long history of photography concerning colonialism, it is impossible not to see through the way these innocent visual explorations manage to take over one's imagination of the distant places.

They continue to form a particular narrative which is further fueling the idea of multi-planetary expansion. Nowadays, one doesn't have to be in space to occupy it; the camera does it for you.

But at the same time, I am looking into ways how these images can tell a different perspective, as mentioned earlier, through failures which refer to the non-human presence, various elements, hostile conditions removed from our 'experience' of the other planet.

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist, Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist, Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA's Mars rover, which took the images that you are using in your project is named "Curiosity". Other NASA missions were named "Discovery', Pioneer', 'Voyager', 'Glory '. This desire to explore interplanetary territories is kind of "collective desire" of human civilization. What could be the artist's role in fulfilling this innate desire?

The artist's role is to be critical and reflect on the origins and the framework according to which collective desires are based on.

These titles reflect the innate curiosity to explore and seek understanding and explanation. However, the artist should provide a critical distance which is necessary for creating space for otherness, to escape reduction of human knowledge and de-center established modes of knowledge. Now we know more about the Martian surface than our own planet by rendering it into a Google object, which can be further analyzed and traversed.

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist, Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Recently, the first image of a black hole was created. It was captured by eight terrestrial telescopes situated in different places, cooperating together to act as one enormous detector - "camera". However, it is questionable whether we can call it a photograph. A black hole is a non-light object, something from which no light can escape, while the word photography means "writing with light". Therefore, it can be said that photography exceeds its own possibilities - captures the invisible. But actually, it's not a light image, it's a radio image consisting of radio waves. How do you think, where are the boundaries of the definition of "photography"? What the future of photography will look like?

It seems that the future of photography is best described in the context of the scientific instruments and their capacity to render visible something which usually escapes the realm of vision and belongs to the world of calculations. Besides, our lives, palms and eyes are attached to the screens, which continuously capture our movements and surroundings whether we are online or offline, forming a unique substance of how we perceive the 'world', and how we are perceived as data-subjects and so on.

Perhaps, when thinking about photography in the ever-growing landscape of new imaging technologies what becomes clear is that we should move beyond the lens-based understanding of photography, and toward the aperspectival and the invisible layers that function silently in the making of digital images, in the making of our relation to and with the 'world' (e.g. algorithms).

Your proposed example exposes that at the heart of image-making is an act of outlining the invisible, something that exceeds the image and at the same time makes it. Like in the 'photograph' of the black hole, what is visible in that image is the heated matter swirling around the black hole exposing its all-absorbing gravity. What is captured there is the process that allows us to grasp the invisible: communication between telescopes, radio waves, distance from Earth, matter, and a given opportunity to 'see' in an attempt to comprehend that which is out of the human reach. This image epitomizes the scale of the phenomenon, the power and resources it takes for it to appear on our screens. As you suggested, it exceeds the established notions of photography as 'writing with light'. And it exposes 'photography' more like a calculating entity, swallowing matter (like a black hole) and turning it into data, removed from visibility but acting as the main point of gravity.

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

In your book "Bodies Inside Out", you talk a lot about the difference between fully absorbing imagery rather than simply perceiving it in the context of experiencing moving image/new media installations. The current situation related to the COVID-19 pandemic led many of us to make the attempt of temporarily replacing or simulating an actual exhibition/installation experience with one in front of a computer screen. Nevertheless, the results have been quite modest. Lots of artworks have been conceptualized specifically for being experienced in real space. This question is about the possibility of corporeal experience through the screen and for the conceptualization of exhibitions which not only 'kind of' work online, but actually work best as virtual exhibitions. Do you feel this is a possibility? For example, I recently read that "blue light", which is what most media devices are using, tells your body that it's morning - that's the hue the sun has in the morning. Yellow light is specific to sunsets. So with blue light, you're constantly kept on high arousal specific to waking up. It disrupts your circadian rhythm and keeps you on high alert. Doesn't that suggest a type of corporeal experience?

Although in "Bodies Inside Out" I focused on the conceptualization of moving image installations in relation to the digital technologies, I certainly agree that there is another layer to thinking about the corporeal experience concerning the digital screen we live with every day. As you suggested, the pandemic has revealed the bodies as screens and screens acquiring a bodily presence because of the constant 'zooming' experience, also all museum exhibitions and 'experiences' moving online. Not to mention the continuous physical fatigue from this connection via screen as the main 'window' allowing one to enter and participate in what was globally taking place.

'Self-portrait on Mars during the sandstorm' from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Courtesy of the artist, Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist

Concerning this hybrid online and offline existence, it might be helpful to go back to the very origins of the term of photography as the light which inscribes itself upon the body. George Didi-Huberman writes about radical meditation practices by Philotheus of Sinai devoted to reaching the truth by exposing himself to the sun of the Sinai desert by staring into the sun until it blinded him: 'At this point, the corporeal vision became a spiritual vision, and Philotheus had become a receptacle for the light that quite literally inscribed itself upon him (photeinographeisthai) (Didi-Huberman, Phasmes, 1998: 49–56)’.

I find this association quite remarkable when thinking about the way the digital screen and the light it emits as integral elements from our everyday experience, the 'blue light' inscribing itself upon us. Perhaps, the idea of a virtual exhibition could be effective if it is thought through technology it is viewed through and engaged with. Otherwise, it becomes another platform to display works like a white cube space which removes the artworks from their context.

Rather than copying and transporting the usual exhibition viewing experience (moving in 3D space), maybe the possibility of a virtual exhibition lies in its experimental mode and readiness to engage with one's corporeal experience directly.

Remaining on the topic of possession, the relation between the virtual and the corporeal - we can only experience other planets from imagery. In the beginning of photography, images were linked to experience, a very special one, because although two-dimensional they were able to create the illusion that people could hold on to the present, possess a moment, study it from the surface of the photograph. The value of a photograph is directly linked to the viewer's in/ability to relive the depicted moment. Today, this experience is probably reserved only for images of intimate value, such as photographs of deceased loved ones. Images of food and sunsets are not only ubiquitous themselves, but so are the experiences linked to them, leaving those photographs with no actual value. On the other hand, we perceive appropriated archival images whose context we're completely unaware of, as valuable objects, although often we know nothing about them. This 'honor' is also reserved for images of planets - as looking at a photograph is our only way of 'experiencing' them, our imagination is drawn to them like a magnet. We might never get to Mars ourselves, but at least we can possess its image and study it. I would argue that this is what makes the depicted texture of Mars in your photographs so attractive and mesmerizing. The longing, the illusion that it is Mars, even when it is not, is so strong that looking at an image becomes a corporeal experience. Could it then be said that the degree of unattainability in the subject of the photograph is directly connected to our ability to experience it? That the actual experience of an art object is rooted in something more than just the physical act of being in its presence? What would that then mean in the context of the virtual exhibition?

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist

I like the idea of unattainability as a condition giving the texture of experience, and forming it as such.

Desire is an underlying structure allowing this possessive moment and emotional involvement in an attempt to engage and imagine something that cannot be directly experienced. Maybe that's why I am attracted to images, still or moving. They already suggest this unattainability in their very form, something extracted, captured, removed, without a body, but a trace, which becomes this very affective, mesmerizing experience involving the entire body, a desiring movement.

It depends on the specifics of the artwork and what it intends to do, but I agree that there is another important dimension, which is related to the imagination and how our bodies are put to work to be able to feel and engage, for example, with the image on the screen, without being in front of a physical art object. But if we are talking about the context of the virtual exhibition, maybe the screen itself acquires a function of the dazzling rectangle of the 'blue light', which inscribes itself upon our bodies, similarly to Philotheus's corporeal experience of the object of his meditations.

Untitled from "You Belong to Me" by Geistė M. Kinčinaitytė, series 2014-ongoing, Copyright and courtesy of the artist, Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech